Two Gates: Hillel Halkin Revisits Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Life and Literature

by LEAH FALK

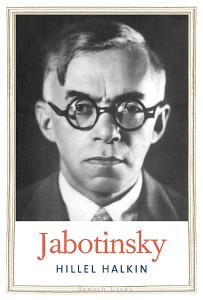

This month, The Jewish Lives Series at Yale University Press releases Jabotinsky: A Life by Hillel Halkin, the first English-language biography of the divisive Odessa-born political leader, novelist, and journalist in nearly twenty years. Why revisit Jabotinsky’s legacy now, and why in English? On Wednesday, Halkin addressed these questions via Skype, from the living room of a friend in Israel. For years after his death, Halkin says, Jabotinsky’s complexities went unexplored, and Jews on both the left and the right used his image as rhetorical ammunition. A two-volume biography by Shmuel Katz, published in 1996, was recognized as a major life of Jabotinsky, but was criticized for its ideological bent. “Katz’s biography is not in some ways critical of Jabotinsky,” says Halkin, “It’s not aware of some of Jabotinsky’s problematic sides. In some ways, my book is a corrective to the stereotypical views of Jabotinsky on the left and on the right.”

How to re-examine a man whose political life kept him almost constantly in the public eye? In previous writings, Halkin has focused on Jabotinsky’s well-respected fiction—in particular, his novel The Five—as a portal into the leader’s conception of himself in relation to the Zionist cause. The Five follows lives of five children in an Odessa Jewish family between the wars. While Jabotinsky saddles each child with a symbolic relationship to Jewishness – one converts to Catholicism, one becomes a Communist – an autobiographic dimension isn’t immediately apparent in the text. But eventually the eldest daughter, Marusya, comes into relief as Jabotinsky’s alter ego. At the novel’s end, she dies in a fire after first saving the life of her son. Before the fire consumes her, she flings the key to her apartment out the window. Halkin sees in this episode Jabotinsky’s martyrdom, his willingness to devote himself entirely to the Zionist cause.

Why do we have to look to Jabotinsky’s fiction, rather than his autobiography Sippur Yamay (The Story of My Life), to tap into Jabotinsky’s romantic conception of his political role? Halkin sees it as the difference in narrative liberty allowed by the two genres: a novelist, under the auspices of fiction, can declare the truth loudly, while a nonfiction writer (particularly a politician) has less freedom. Despite his prolific literary output and what it reveals about his life and politics, Jabotinsky seemed to feel that to be both a statesman and a man of letters was contradictory. In his autobiography, Halkin says, Jabotinsky recounts a dream in which he arrives at two gates. One is “the gate to literature, and the other is the gate to the Jewish people.” He chooses the latter, as if to choose both was not an option. Revisiting his life, a biographer might also feel torn between “two gates” – Jabotinsky’s life in letters or in Zionism. But to Halkin, who sometimes wonders if Jabotinsky chose correctly by limiting his involvement in literature, the two entrances of Jabotinsky’s dream are inextricable from each other.

Halkin is not the only one interested in presenting a more complex portrait of the giants of Zionist and Israeli history. In 2012, HaBimah presented Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua’s play Can Two Walk Together? which dramatizes a series of meetings between Jabotinsky and founding Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion in London in the 1930s. Among both Israeli and American Jews, Halkin notes, Israel’s ongoing political struggles have provoked renewed interest in the complexities, commonalities and flaws of the country’s early leaders.

Halkin, along with New York Times cultural critic Edward Rothstein, Columbia professor of history Rebecca Kobrin, and Jewish Review of Books editor Abe Socher will discuss Jabotinsky: A Life on June 2, 2014 at 7 pm at YIVO. Co-presented by YIVO, Yale University Press, and the Jewish Review of Books.

Attend the program.

View a poster for a 1929 lecture by Jabotinsky.

Leah Falk is YIVO’s Programs Coordinator.