If Books Could Talk: The Story of Three Jewish Treasures Rescued from the Vilna Ghetto

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

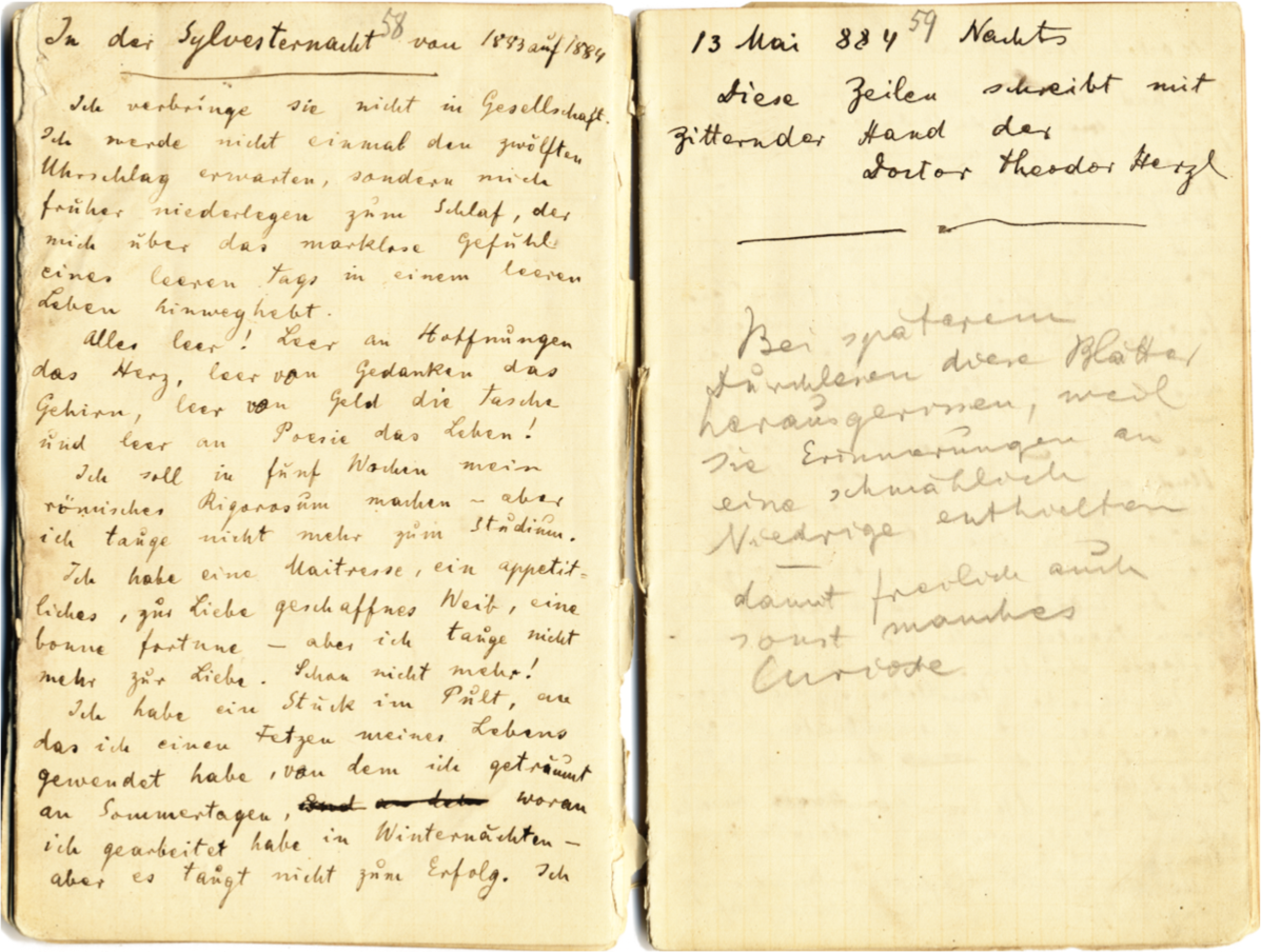

Diary of young Theodor Herzl, kept from 1882 to 1887. YIVO Archives.

Diary of young Theodor Herzl, kept from 1882 to 1887. YIVO Archives.On Monday, November 24, at 7:00pm, Professor David E. Fishman will deliver a lecture at YIVO, “If Books Could Talk: The Story of Three Jewish Treasures Rescued from the Vilna Ghetto,” about three artifacts rescued from looting by the Nazis in Vilna (present day Vilnius, Lithuania):

- Theodor Herzl’s diary

- The minute-book from the Vilna Gaon’s synagogue

- An original manuscript of Jacob Gordin’s classic Yiddish play Mirele Efros.

Two of these works made their way to YIVO in New York after World War II, but the third work encountered a very different fate in Soviet Lithuania.

“There were a lot of Jewish collections in Vilna and they all had the same fate during World War II,” Fishman notes. When the Germans occupied Vilna in 1941, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), a special task force which operated throughout Nazi-occupied Europe to loot Jewish cultural treasures, sent a team to Vilna, a city rich in Jewish history and culture. There, the ERR established a collection center for their loot in the YIVO building at 18 Wiwulskiego Street. A group of slave laborers was put into place to sort the books, documents, and artifacts stolen from institutions and private collections. Items deemed “valuable” were sent to Germany to the Institut Zur Erforschung der Judenfrage (Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question), while other items were slated for destruction.

The sorting team, which included some prominent members of the Jewish community, such as young poets Abraham Sutzkever and Shmerke Kaczerginski; YIVO scholar Zelig Kalmanovitch, and librarian Herman Kruk, mounted a secret resistance to the looting. They risked their lives to rescue rare documents, books, and artifacts, smuggling them out of the workplace, to hiding places in the ghetto or to non-Jewish friends for safekeeping.

“It was an act of faith that there would still be a Jewish people in the future and that it would need its cultural heritage—it was a belief in the importance of culture,” Fishman reflects. “You could die any minute, but even so, they held onto the belief that being a human being involves more than eating and drinking. Being a human being also needs an enrichment of the soul.”

After Vilna’s liberation from the Nazis in 1944, the few members of the sorting team who survived came back to the city and retrieved whatever they could find of the hidden materials, sometimes digging them out of bunkers. They created a Jewish Museum. “But they rather quickly lost hope in the viability of Jewish life in what was now Soviet Vilnius.” It was obvious that the material would not be made available to the public, given restrictive Soviet censorship policies. “The materials might physically survive but no one was going to be able to read the books or study the archival materials. And it began to be clear that there were no resources to deal with them properly, that the state was not going to provide the resources for proper cataloging. The museum had a small staff and the authorities were rather begrudging about its existence.”

The Jewish activists now devoted themselves to smuggling as much of the materials as they could out of Lithuania to YIVO, which had since relocated to New York, and had with the help of the U.S. Army, been able to recover some of the material shipped to Germany from Vilna during the war.

“That was a very interesting moment, when they realized that all their tremendous efforts and labor to rescue the material from the Germans might be in vain if they stayed in this type of controlled Soviet institution—that they would have to rescue the materials yet again,” Fishman points out. The museum was closed in 1949.

Some of the books and documents remaining in Vilnius were destroyed. “The materials were in piles and mountains,” Fishman notes. “The piles were in different places and sometimes the municipal authorities would come by and collect what they considered garbage and send it away to be destroyed.” For several years, it was assumed that whatever hadn’t made its way to YIVO in New York was lost forever. But in 1988, it was revealed that tens of thousands of books and documents had survived, hidden by a brave Lithuanian librarian, Antanis Ulpis, in the basement of the Lithuanian Book Chamber. (Today, these materials are in the collections of the National Library of Lithuania and the Lithuanian Central State Archives, which are cooperating with YIVO in a project to digitize them and make them available online. See “Split Up By the Holocaust, Top Collection of Yiddish Works Will Reunite Digitally.”)

Professor Fishman first published a short book on the subject of YIVO’s looted collection, Embers Plucked from the Fire: The Rescue of Jewish Cultural Treasures in Vilna, in 2009. He is now working on a full-length book on the fate of Jewish materials in Vilna under the Nazis and the Soviets. A professor of Jewish History at The Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), he serves as director of Project Judaica, a Jewish-studies program based in Moscow that is sponsored jointly by JTS and Russian State University for the Humanities. He is the author of numerous books and articles on the history and culture of East European Jewry, including Russia's First Modern Jews (New York University Press) and The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture (University of Pittsburgh Press). He has taught at universities in Israel, Russia, Ukraine and Lithuania, and serves on the editorial boards of Jewish Social Studies and Polin.

Attend the program.